FR

CREAM

« Ceci n’est pas un travail sur le Handicap ».

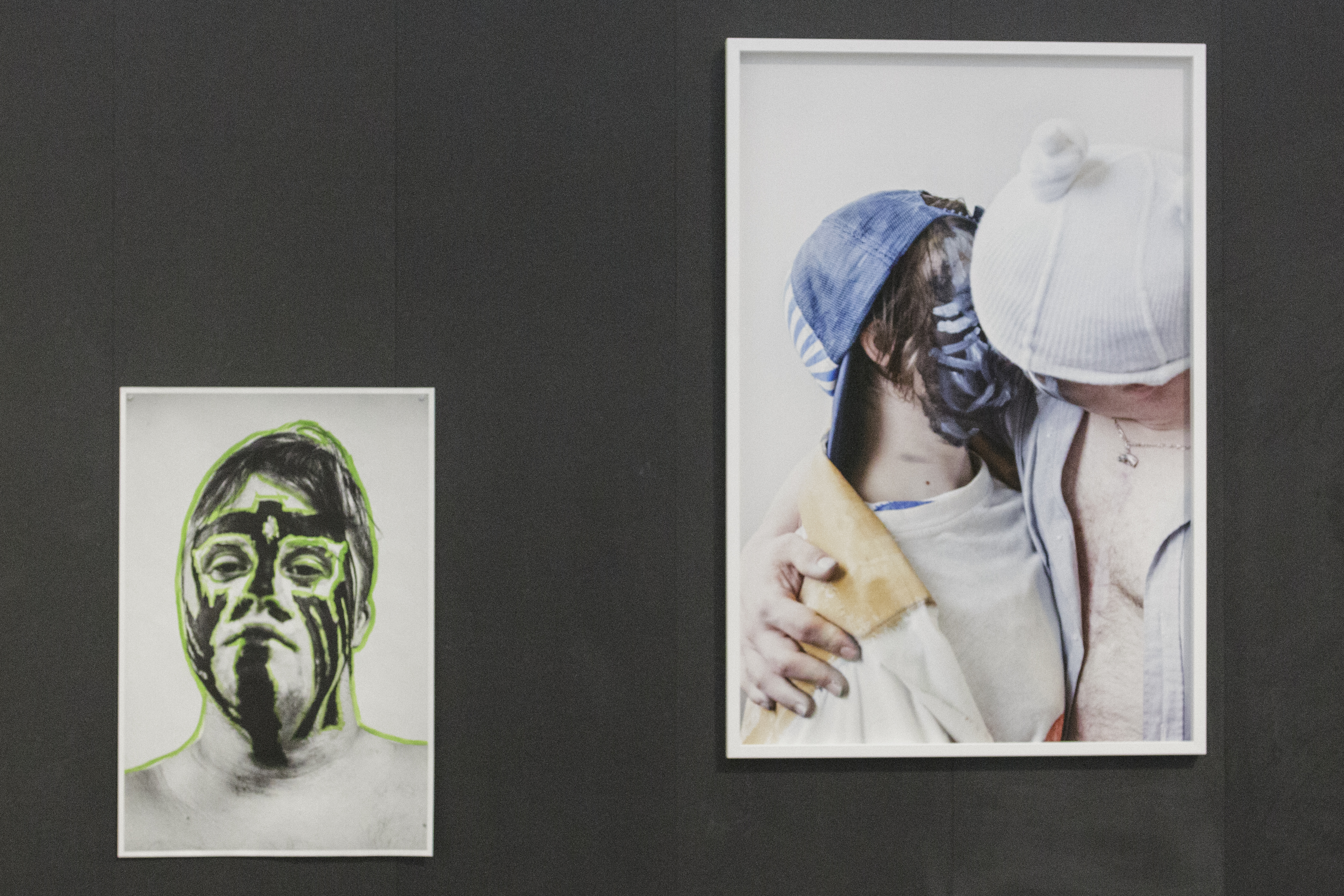

L’installation proposée par Laetitia Bica reprend une chorégraphie ontologique de deux mois. Commencée avec « la crème de la crème » artistique au sein des ateliers du Creahm (Créativité et Handicap Mental), la performance s’est continuée ensuite lors d’une résidence au RAVI (Résidences Ateliers Vivegnis International) en compagnie de l’artiste-samouraï Samuel Cariaux, ainsi qu’au sein de l’atelier Bruno Robbe. Cette expérience hérite de plusieurs années de travail durant lesquelles la photographe a poursuivi son exploration de l’être-en-commun, des recouvrements et des agencements plastiques.

La notion de chorégraphie ontologique a été forgée en 2005 par l’anthropologue Charis Thompson pour décrire la manière dont les couples lesbiens négocient, par inclusion du donneur tiers, leur place en tant que « vrais parents » de leur enfant, sans fermer la possibilité d’une autre mise en récit. Elle a en suite été reprise par la philosophe Donna Haraway sur le plan conceptuel pour penser ce qui se joue dans les « zones de contact » entre les êtres vivants – humains ou non-humains –, en mettant l’accent sur la manière dont ces espaces de jeu métamorphosent, par « induction réciproque », le mode d’existence des êtres mis en relation. Durant cette performance, commente la philosophe Isabelle Stengers, « deux êtres autres font (...) l’expérience d’une co-présence inventive – expérience de co-préhension plutôt que de compréhension ».

La possibilité d’une telle co-présence inventive s’est vite posée comme enjeu important dans la collaboration entre les artistes. Chaque partenaire, en effet, a ses routines, ses habitudes, ses petites recettes qui lui permettent de fonctionner et de persister, de maintenir une continuité de trajectoire dans des milieux changeants, où chaque rencontre est occasion de bifurcation. Cependant, la répétition génère un excès infime sur ce qu’elle réitère. Il n’y a de reprise que « différante ».

C’est là que l’instauration du partenariat devient matière à risque. Il n’y a pas de jeu entre les partenaires tant que les petites différences réciproquement induites dans la collaboration n’ont pas atteint le seuil du remarquable, par quoi elles sont susceptibles d’être remises en jeu. Le danger, dans le cadre de chaque collaboration artistique, était de sauter l’épreuve d’apprentissage requis pour que ces nouveautés produites dans la répétition soient perceptibles. Il fallait donc éviter que la réussite du partenariat soit subordonnée aux formes conventionnelles de la « compréhension mutuelle ». Car la bonne raison communicationnelle, censée mettre tout le monde d’accord, devient alors l’occasion d’une prise de pouvoir qui ne dit pas son nom, où le gagnant est celui qui s’octroie le droit de rendre raison de l’activité de l’autre.

On ne sort de cette ornière dialectique qu’en invitant le tiers. « Un tiers survient, qui n’a aucun rapport aux êtres ou aux choses, mais qui n’a de rapport qu’à leur relation même », écrit Michel Serres. La raison communicationnelle repose sur la logique du tiers exclu, c’est-à-dire d’une mise hors-jeu de ce qui « instaure » la relation. L’autonomie et l’indépendance supposée des individus n’est d’ailleurs pensable qu’au prix d’une telle hypocrisie ; par quoi l’exclusion du tiers se tient elle-même sous le seuil critique du remarquable. Et comme le démontre l’argument platonicien du « troisième homme », la série des intercesseurs n’a pas de fin : l’inclusion du tiers sur la scène communicationnelle se fait par exclusion d’un autre tiers, dont l’inclusion en requiert un troisième, et ainsi de suite, à l'infini.

En impliquant la série exponentielle de ses dépendances, la chorégraphie ontologique témoigne pour la vie dans ce qu’elle a d’« asocialement inséparée ».

Jeffrey Tallane

EN

CREAM

“This is not a work on Disability.”

The installation by Laetitia Bica recaps a two-month ontological choreography. Initiated with the artistic “cream of the crop” in the studios of CREAHM [Creativity and Mental Disability], the performance was subsequently continued during a residence in the RAVI [International Vivegnis Studio Residencies] together with samurai artist Samuel Cariaux, as well as in the workshop of Bruno Robbe. This experience has been gained over several years of work during which the photographer has pursued her exploration of the being-in-common, plastic arrangements and recoveries.

The term ontological choreography was coined by the anthropologist Charis Thompson in 2005 to describe the way lesbian couples negotiate their place as “real parents” for their child, , by including the third donor and without excluding the possibility of another narrative. It was then taken up conceptually by the philosopher Donna Haraway to consider what is played out in the “contact zones” between living beings (human and non-human). She stresses the way these play areas transform, by “reciprocal induction”, the mode of existence of those beings that are in relation which each other. During this performance, the Philosopher Isabelle Stengers points out, “two different beings make (…) the experience of an inventive co-presence – an experience of co-prehension rather than comprehension.”

The possibility of such an inventive co-presence rapidly emerged as a major issue in cooperation between artists. Each partner in fact has his routines, habits, and little recipes that enable him to function and to persist, to maintain a continuity in changing environments, where each encounter is an opportunity for bifurcation. Nevertheless, the repetition generates a slight excess on what it reiterates. There can only be a differing rework.

This is where the inception of the partnership becomes risk material. There is no play between the partners as long as minor differences reciprocally induced in the cooperation have not reached the threshold of the remarkable, at which point they can be challenged. The danger, in any artistic cooperation, lies in skipping the apprenticeship trial required so that the novelties produced in repetition are perceptible. Care had to be taken therefore to avoid having the success of the partnership subordinated to the conventional forms of “mutual comprehension.” For then, the right communicational reason, deemed to get everyone to agree, turns into an opportunity for a power grab that will not speak its name, where the winner is the one who appropriates the right to agree with the activity of the other.

The only way out of this dialectical rut is to call in a third party. “A third party arrives that has no relation with the beings or the things, but only with their relation itself,” Michel Serres writes. The communicational reason rests on the rationale of the excluded third party, i.e. an offside of what “instaurates” the relation. The supposed autonomy of individuals is for that matter conceivable only at the price of such hypocrisy, through which the exclusion of the third party is maintained below the critical threshold of the remarkable. And as Plato’s “third man argument” shows, there is no end to the series of intercessors: a third party is included in the communicational scale by excluding another third party, whose inclusion requires a third, and so on ad infinitum.

By implicating the exponential series of its dependences the ontological choreography testifies to life as “asocially inseparated”.

Jeffrey Tallane